Spring 2024 Corn Belt Planting Outlook

A very different and currently less predictable spring is shaping up for Corn Belt farmers, according to weather models in late-January.

After three consecutive years of La Niña-influenced spring planting seasons, a super El Niño is peaking now and may not diminish until summer or fall. Historically, this rare and strong weather phenomenon (almost two degrees above average) reverts quickly to a La Niña.

“The speed at which El Niño decays will be a huge factor in what happens this spring and summer,” says John Baranick, DTN ag meteorologist. “Weather models are all over the place, so there’s no confidence that this strong El Niño will follow a typical quick-exit route.”

This El Niño has been super strong since September, whereas a more normal El Niño will last nine to 12 months.

The longer these higher Pacific Ocean surface temperatures along the equator last, the longer it brings warmer and drier weather across the Corn Belt. The jet stream will bring moisture along a southerly track from California through Texas and into the southeastern U.S., bypassing the Midwest.

Baranick examined two analog years influenced by a strong El Niño: 1998 and 2016. In 2016, the Midwest was warm in April and May, with more moisture in the Plains and a drier eastern Corn Belt. In 1998, April was colder, and May temperatures rose dramatically with little rainfall.

“These two years flip-flopped, with April being warm in 2016 and May being hot in 1998, Baranick says. “We’re probably going to see a lot of temperature and precipitation variability this spring. It’s difficult to decide where the hot/dry and wet/cold areas will occur right now.”

Even though weather models disagree on the details, they share a dry bias for spring. Baranick currently sees a dry April and May across the Midwest as El Niño trade winds carry southbound moisture.

Farmers with adequate moisture will likely get crops off to a good start. However, sustaining good growth during late spring when the temperatures heat up is difficult without subsoil moisture or timely rains.

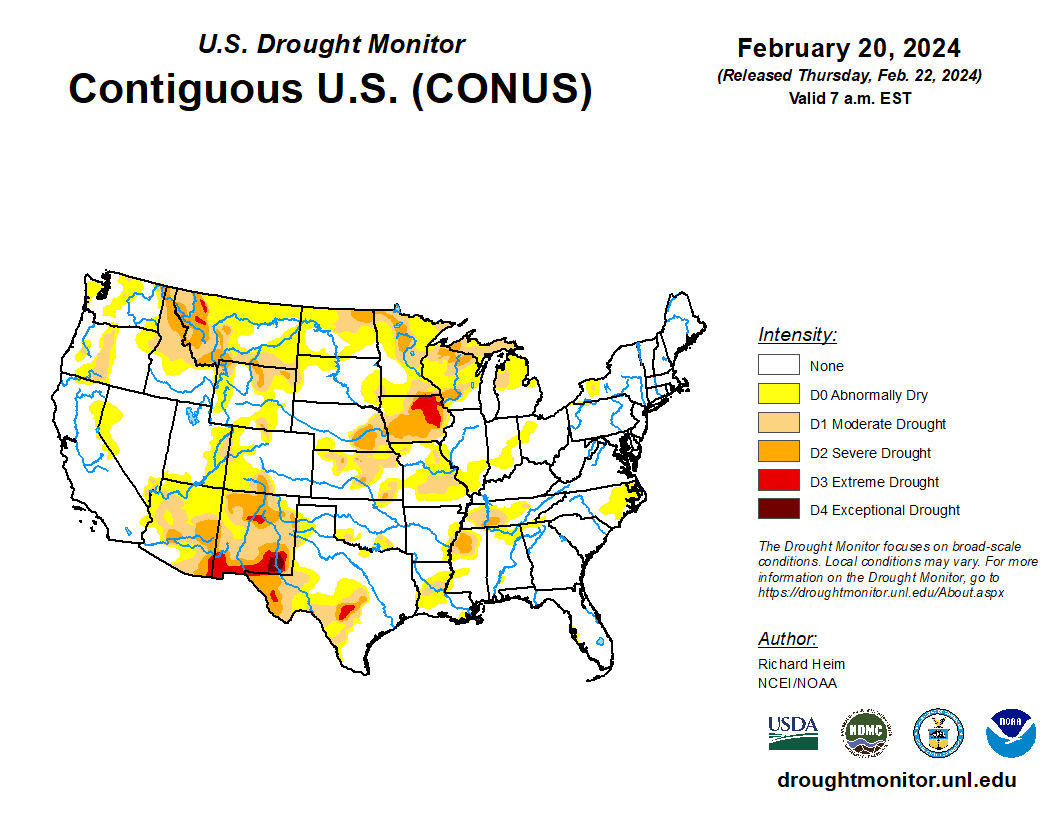

Good rainfall last summer diminished severe drought in numerous areas, yet drier portions of states remain with inadequate subsoil moisture.

The drought monitor shows bands of dry areas from central Kansas and eastern Nebraska into Iowa and portions of Minnesota and Wisconsin. Another Corn Belt dry band stretches from Missouri and southern Illinois into Indiana and western Ohio.

“The currently dry Corn Belt areas will probably stick around,” Baranick says. “El Niño doesn’t bring much rain to the eastern Midwest around the Great Lakes or the Ohio Valley.”

Numerous forecasts show a late-summer to early-fall development of La Niña, but the U.S. model and DTN meteorologists currently forecast an earlier arrival.

“Honestly, I’m most concerned about a dry summer in the Corn Belt if La Niña arrives this summer,” Baranick says. “Early arrival often translates into a stagnant high-pressure ridge in the western Corn Belt. However, history shows that a super El Niño pushes that ridge into the eastern Corn Belt. So, instead of the western Midwest bearing the brunt of the worst conditions, this pushes hot and dry weather throughout the Corn Belt.”

If El Niño hangs around longer as some models predict, leading to more neutral conditions in the summer rather than La Niña, then the Corn Belt may see more regular thunderstorms. The closer the Pacific Ocean temperatures are to an average state, the more other climate drivers can control weather patterns. For example, the Madden-Julien Oscillation (MJO) could bring more frequent periods of thunderstorms and ocean temperatures in the Atlantic could drive deeper storm systems across the U.S. to produce more widespread rain.

Baranick reminds growers to take a wait-and-see approach, as current models provide a low-confidence forecast. “We need to see how La Niña shapes up over the summer. But there are currently big risks out there as we head into La Niña,” he adds.

Content provided by DTN/The Progressive Farmer

Find expert insights on agronomics, crop protection, farm operations and more.